What is the Ocean Worlds Initiative?

The examination of ocean worlds provides opportunities to compare Earth and other planets. This is incredibly important for our understanding of extraterrestrial life, and also our understanding of the origin of life on Earth billions of years ago. Additionally, our comparative studies allow us to examine Earth's ability to sustain life through the present and future through changes in Earth's surface.

Present National Programming

NASA has multiple ongoing programs that are evaluating aspects of Ocean Worlds in our galaxy, including, at present, the following missions and networks:

NASA Astrobiology has formed the Network for Ocean Worlds (NOW), a research coordination network specifically to look at the interiors, oceans, and cryospheres of other extraterrestrial ocean worlds. The goal is to look at how habitable these worlds are, determine if there is already life on them, and to contextualize life on this planet. NOW began meeting in 2019 with ~50 relevant scientists present representing interdisciplinary interests.

NASA's Europa Clipper will orbit Jupiter and will make regular dives (up to 49) close to Europa's surface during flybys while in orbit around Jupiter. More information can be found at NASA's Europa Clipper Webpage, and images and multimedia showing its preparation for launch can be found at NASA's science mission website.

The proposed Europa Lander Mission will send a spacecraft to the surface of Europa to select surface and below-surface samples. This spacecraft will have a miniature laboratory, not unlike the ones on prior Mars rovers, where it will conduct analyses on these samples.

The New Horizons mission is another interplanetary space probe launched by NASA's New Frontier Program and managed by the John Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory and the Southwest Research Institute. The New Horizons mission was launched in 2006 to examine Pluto and objects on the Kuiper belt . While examining Kerberos, a moon of Pluto, the New Horizons spacecraft noted observations suggesting a surface of clean water ice.

Present International Programming

In addition to NASA, government space agencies in other countries are involved in Ocean Worlds explorations. This includes agencies such as the ESA (European Space Agency: representing 20 constituent countries) Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), Roscosmos State Corporation for Space Activities (Roscosmos), the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), the China National Space Agency (CNSA)

The Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE) is a mission run by partners in the European Space Agency (ESA) to explore Jupiter, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede (three of Jupiter's icy moons). JUICE is a single orbital spacecraft without a lander, and is the first satellite to orbit a moon that isn't Earth's moon. JUICE launched in 2023 (April 14th) and will hopefully reach Jupiter's orbit by late 2031, where it will then stay for 3 years. If all goes as planned, it will then begin orbiting Ganymede, which is the primary moon of focus for this mission. This mission follows up on NASA's Galileo Mission (1989-2003) which found evidence of possible liquid water on Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto and complements NASA's Europa Clipper mission (which focuses mostly on Europa).

Past National Efforts

Interest in Oceans Worlds is not new: the understanding of potential extraterrestrial life and closely linked liquid water on other planets has been a priority for NASA for over three decades.

Galileo was a spacecraft launched in 1989 to orbit Jupiter and its moons, particularly Europa. Galileo famously was the first spacecraft to visit an asteroid (Gaspra and Ida), allowed us to witness a comet colliding with a planet, and showed us previously unseen details of Venus' atmosphere. In the 1990s, Galileo discovered the initial evidence of a saltwater ocean below Europa's surface.

Cassini was a spacecraft launched in 1997 to explore Saturn and its icy moons for over ten years. Through Cassini, we learned that Enceladus has the ingredients necessary for life, a lesson that catalyzed the exploration of ocean worlds across the Earth.

Why are we so interested in water?

Hydrogen was the first element created during the Big Bang. Oxygen was created much later in the cores of large stars by nuclear fusion. In our galaxy, and our universe, enormous amounts of water vapor exist. Together, two hydrogen molecules (atomic number: 1) and one oxygen molecule (atomic number: 8) makes water (dihydrogen monoxide: H2O).

Water is absolutely vital to life, and is essential for the survival of every single living species on Earth. But in addition to being instrumental to life, water bodies also provide a mechanism for the recycling of important nutrients critical to life (e.g., Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Iron, Sulfur, etc.) via circulation, buffering of pH due to the dissolution of carbonates into water, and the maintenance of equable temperatures due to the high specific heat capacity of water.

Earth is special and suited to hosting life, as 71% of Earth's surface is covered in water: in other words, water is abundant. There is water on other planets and moons in our solar system, and in fact, there is even evidence of water beyond the edge of our solar system. A critical suite of tools we use to study water and life on our planet and in the solar system is known as “remote sensing.” Remote sensing satellites allow us to monitor water in planetary atmospheres and on planetary surfaces by absorbing light from the oceans, land, and atmosphere. As an example of this, the Hubble Space Telescope found water-building molecules in the Helix Nebula and the Orion Nebula. Water molecules have even been found in planets orbiting the Beta Pictoris star.

Just like us, the origin of our oceans are in the stars. As Carl Sagan famously said in his 1980s rendition of Cosmos, “The cosmos is within us. We are made of star-stuff.” Thus, to understand Earth better, we look to space using remote sensing technology.

Remote sensing technology

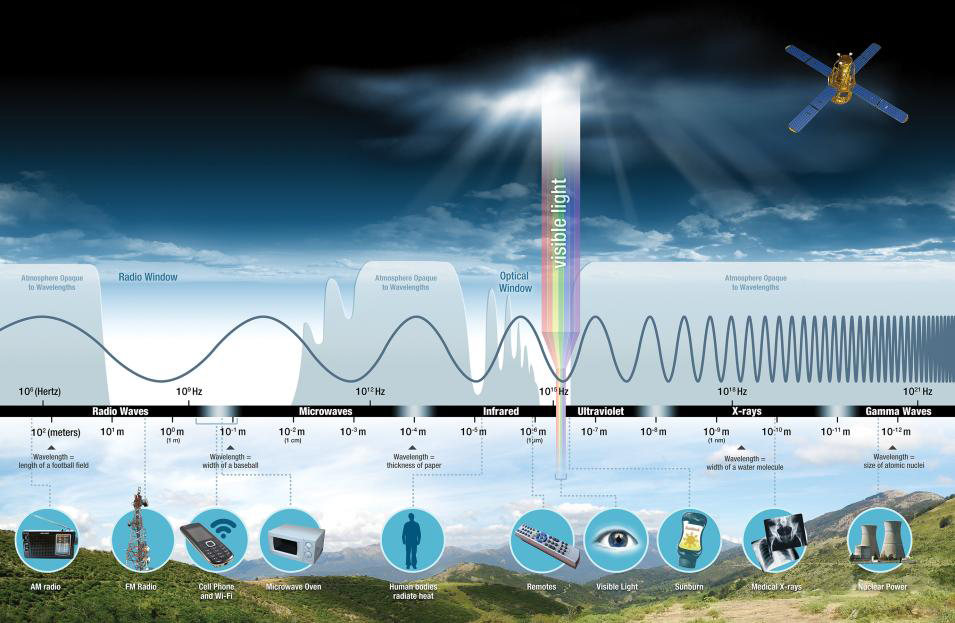

Satellite remote sensing is used to examine Earth as well as other planets and planetary bodies from the vantage point of space. As mentioned, remote sensing is the act of collecting observations from a distance (i.e., remotely). Commonly, when we use the term “remote sensing,” we are referring to sensor technologies on aircrafts and satellites that observe and record reflected or emitted energy along the electromagnetic spectrum.

Three common types of orbits around Earth's surface are low-Earth orbit (160-2000 kilometers about Earth), medium-Earth orbit (2000-35,500 kilometers above Earth) and high-Earth orbit (>35,500 kilometers above Earth, the speed at which they are in geosynchronous orbit). An example of a low-Earth orbit satellite is NASA's Aqua satellite, which is sun-synchronous and polar orbiting , known for collecting information about the water on Earth's surface using its:

- Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS),

- Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer for the Earth Observing System (AMSR-E),

- Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit-A (AMSU-A),

- Clouds and the Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES),

- Humidity Sounder for Brazil (HBS),

- and, Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS)

Another example of a low-orbit satellite includes the joint NASA/Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory. One of the newer satellite imagery missions, dubbed “PACE” (Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystems), launched in February of 2024, provides imagery that allows scientists to even look at microscopic ocean life and aerosols by detecting light across a hyperspectral range.

Medium-Earth orbit satellites take about 12 hours to complete an orbit, so cross over the same point on the equator 2x per day. These satellites are key for telecommunications and GPS. An example of a medium-EArth orbit satellite system is the European Space Agency's Galileo global navigation satellite system (GNSS).

High-Earth satellites include weather satellites like the joint NASA/NOAA Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) series, 35,786 kilometers above Earth's orbit.

Remote sensing works by absorbing energy along the full range of the electromagnetic spectrum, including visible light which reflects photons from the sun at wavelengths we can see with our eyes, but also ultraviolet, x-rays, and gamma rays.

Observing with the Electromagnetic Spectrum: Electromagnetic energy, produced by the vibration of charged particles, travels in the form of waves through the atmosphere and the vacuum of space. Credit: NASA Science

The tools on satellites and aircrafts that use the sun for illumination are called “passive sensors” while “active sensors” provide their own signal. Passive sensors mostly operate in visible, infrared, thermal infrared, and microwave parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, recording things like land and sea surface temperatures, vegetation, cloud and aerosol properties, etc. Passive sensors have difficulty penetrating dense cloud cover and thus limitations observing areas like the tropics on our Earth, where clouds are pretty thick frequently. Passive ocean color sensors using visible wavelengths of light cannot see features when it's dark, making nighttime and polar regions elusive.

Active sensors can operate in the UV, visible and in the microwave band of the electromagnetic spectrum, where they are therefore able to penetrate the atmosphere and thick cloud cover under most conditions. These sensors typically measure the vertical profile of aerosols, forest structures, precipitation, wind, sea surface topography, ice, and more recently, the ocean. In other words, provide a 3-dimensional view of Earth.

There are many different Earth-focused remote sensing imagery tools on the International Space Station (ISS), including visual images as well as hyperspectral and thermally-sensed images. Typically, modern planetary remote sensing technology has been used for topographic mapping (e.g., of Mars, the Moon, the Kuiper Belt)

The technologies we employ to observe Earth and those we use to observe other planets and moons are different. Specifically, because of the proximity of Earth orbit to Earth itself, we are able to study more advanced technologies. NISAR (NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration)-ISRO (Indian Space Research Organization) Synthetic Aperture Radar), the most recent radar mission in space, uses two different radar frequencies (L-band and S-band) to measure changes of our Earth's surface, all the way down to a centimeter – extremely fine resolution! NISAR includes a 12m radar antenna reflector, GPS antenna, deployed radar antenna boom, deployed solar array, L- and S- band feed RF aperture L- and S-band SAR electronics, and L-SAR is capable of 7m resolution along its track across Earth's surface.

Europa Clipper, on the other hand, must be equipped with a higher proportion of propellant (6,000 lbs). While it has 9 dedicated science instruments – the most advanced and sensitive to be sent to the outer solar system yet – and gravity/radio science, it also is weighed down by 24 engines. The nine instruments include:

- a wide and narrow-angle camera with a sensor for high-resolution color images – with resolution of 330 feet per pixel,

- a thermal imager,

- an ultraviolet spectrograph,

- a mapping imaging spectrometer,

- a magnetometer to measure the depth, salinity, and existence of an ocean,

- plasma instrument for magnetic sounding to examine Europa's ocean without magnetic distortion,

- radar for Europa assessment to penetrate the ice,

- mass spectrometer to analyze atmospheric gasses, and

- a surface dust analyzer.

More information on each of these instruments can be found on NASA's Europa Clipper website.

In addition to using remote sensing technology, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory coupled with California Institute of Technology has created an Oceans World Laboratory, where research simulating conditions on other potentially water-bearing moons and planets is conducted on Earth's surface, in both the laboratory and the field.

Life began in the ocean

Evidence supports that life likely began in the ocean >3.5 billion years ago. The first evidence of photosynthesis is from 2.5 billion years ago.

The origins of oceans comes down to water, which originated during the Big Bang, just like every other molecule.

The exact mechanism for the origins of life is unknown, but many hypotheses identify a marine origin. Most recently, theories have narrowed in on the origin of life occurring in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor. These areas are rife with the makings of life: water (the key ingredient), a high-energy and high-flux environment which is warmed by chemical energy from Earth. Understanding the origin of life on this Earth and our informed hypothesis that this occurred in the ocean leads us to target extraterrestrial ocean worlds as potentially habitable.

By 3.5 billion years ago, life was widespread in the ocean and likely mostly in the form of ancient mats of microbes called “stromatolites” that glommed onto sand, minerals, and the floor in the shallow ocean.

Oceans allowed life to become more complicated, too. The first “complex” life forms appeared ~560 million years ago in the oceans. They were soft-bodied and lived at the bottom of the ocean, reliant on absorbing nutrients (like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus) directly, and absorbed simple molecules not unlike bacteria, today. Other organisms covered the ocean floor in thick microbial communities or “mats,” which in turn provided food for ancient ancestors of arthropods (Spriggina, Kimberella, Tribachidium).

Nitrogen and the Ocean

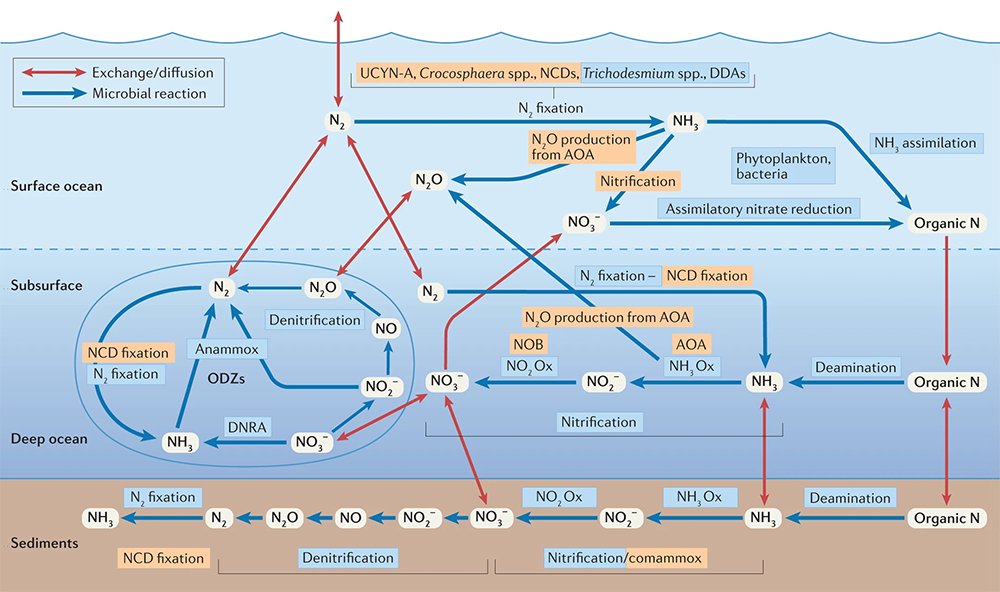

Nitrogen is key in the ocean as a limiting nutrient. Like on land, fixed (biologically available) nitrogen is, along with phosphorus, one of the most growth-limiting nutrients for the base of the oceanic food chain: photosynthetic plankton.

In our oceans today, nitrogen is taken up in its inorganic (e.g., NH3) form by phytoplankton, oxidized (often from NH3 or NO2 to bioavailable NO3-) by bacterial chemoautotrophs, and the reduction of nitrate to N2 gas (the main constituent of the atmosphere), available for atmospheric exchange.

Humans are influencing the nitrogen cycle in the ocean. Specifically, the anthropogenic contribution of nitrogen via agricultural inputs – often made artificially using the Haber-Bosch process – results in a flux of nitrogen into ecosystems where it used to be limited. This causes a major bloom in photosynthetic organisms, which in turn block sunlight and change the oxygen profile of the ocean, totally shifting ecosystems in dramatic ways.

Oceanographic observations were long constrained by ship availability, but now a combination of satellite and drone-based remote sensors with advanced sensors (for example: biogeochemical Argo drifters as run by NOAA), combined with sampling on ocean vessels (e.g., Tara Oceans Project, GO-SHIP hydrography program run through US CLIVAR) have opened up space for ground-truthing satellite data. As such, we are now able to make assessments on planetary nitrogen in oceans in a way that was previously impossible.

On Earth's surface, blooms of phytoplankton thriving on nitrogen and phosphorus that are often a product of agricultural runoff are detectable from space. The recently launched PACE mission is an important remote sensing tool involved in collecting data on these observable phytoplankton blooms.

Nitrogen has been detected on Ocean Worlds, such as Enceladus (specifically detected by Cassini: acetylene, ammonia), Triton, and even Pluto.

Phosphorus and the Ocean

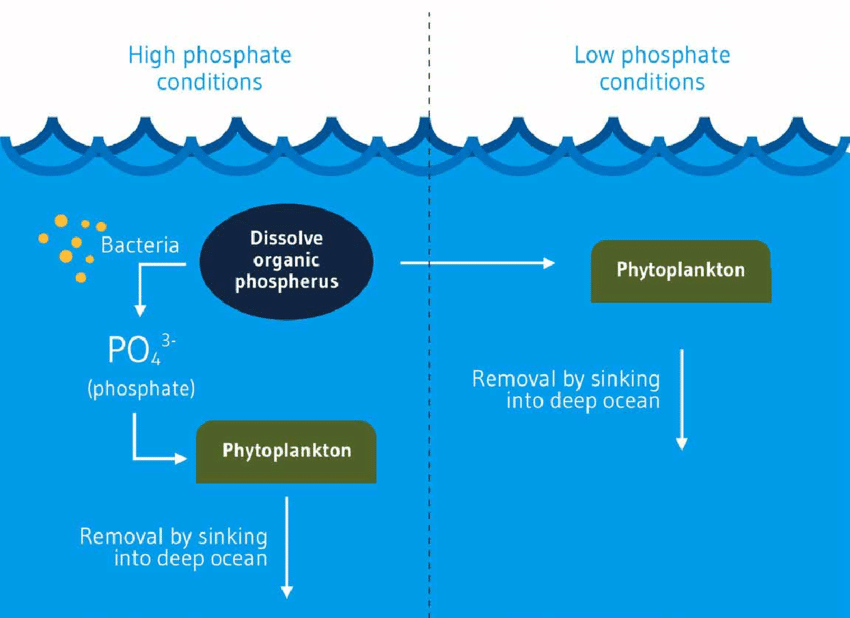

Phosphorus is a limiting factor for life in many ecosystems. Phosphate is a key component in genetics and in the way we move around energy via adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Phosphorus in the ocean promotes the production of microbes and tiny phytoplankton which in turn are eaten by higher organisms on the food chain.

Eventually, phosphorus in these organisms sinks to the ocean floor as the organisms die. This phosphorus on the ocean floor eventually forms new sedimentary layers. Over long periods of time and with plate tectonic-driven uplift, these new sedimentary rocks can be brought to the land surface, where they experience chemical and physical weathering that releases phosphorus for organisms once again.

Phosphorus cycle in the ocean. Phosphorus is required by

all living organisms to make DNA, RNA, ATP (energy

molecules), and other essential organic compounds. The

most abundant phosphorus exists in the form of

phosphate.

Image credit:

Kwong 2015

On Earth's surface, blooms of phytoplankton thriving on nitrogen and phosphorus that are often a product of agricultural runoff are detectable from space. The recently launched PACE mission is an important remote sensing tool involved in collecting data on these observable phytoplankton blooms.

Given the importance of phosphorus for life, its abundance in extraterrestrial settings is a point of interest for many scientists. As several moons in the outer solar system (e.g., moons of Jupiter and Saturn, for example), host liquid water, scientists at NASA Ames Research Center have modeled dissolved phosphate across a range of starting rock and water states for these moons. Findings indicate that many of these moons may have enough phosphate concentrations to support life.

Phosphorus has been found in a bioavailable form (as phosphate) in Enceladus' Ocean by Cassini's Cosmic Dust Analyzer. In fact, Enceladus has significantly higher concentrations of phosphorus than Earth does.

pH, Carbon, and carbonates

The carbonate system is an incredibly complex and important part of oceanic chemistry, and plays an important role in the carbon cycle (which is critical to life). The carbonate system also controls the acidity (pH) of water. The carbonate system is complex, and includes a number of different species of carbon oxides (carbon dioxide: CO2, carbonic acid: H2CO3, bicarbonate: HCO3-, and carbonate: CO32-).

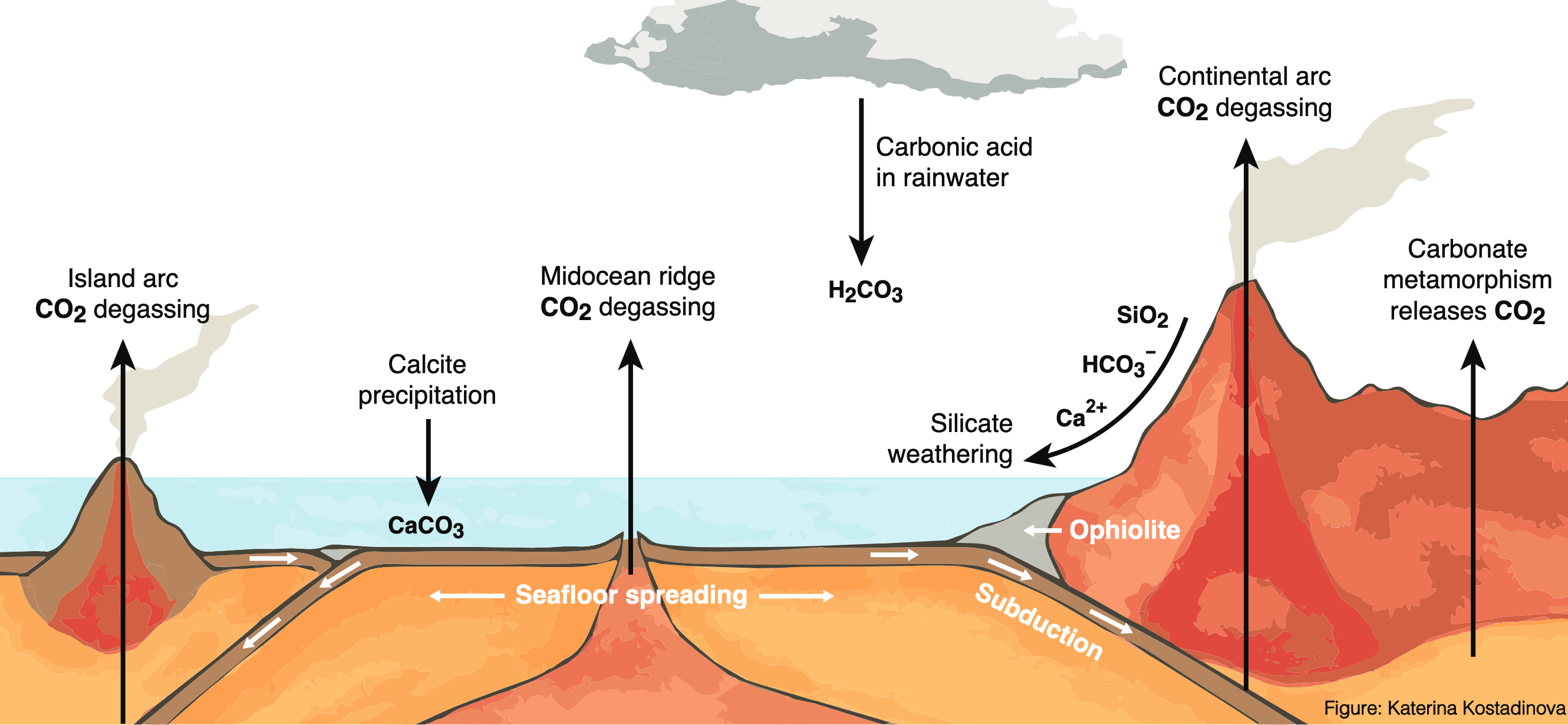

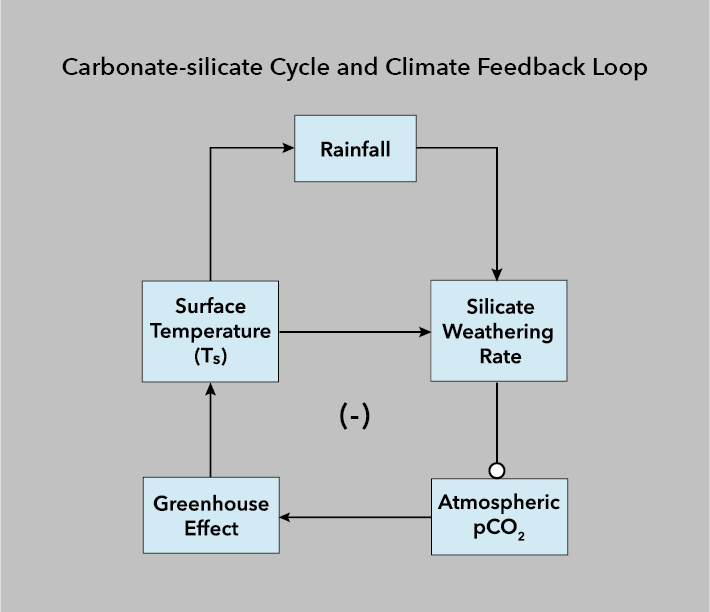

The carbonate-silicate cycle is a natural feedback system that maintains Earth's long-term stability. It involves the a) weathering of silicate rocks, b) transport of dissolved ions to the ocean, c) formation of carbonate minerals, d) and subduction of these minerals into the mantle, where they are eventually released as CO2 through volcanic eruptions.

This cycle acts as a long-term thermostat for Earth's climate. When atmospheric CO2 levels rise, the weathering of silicate rocks accelerates, drawing down CO2 and cooling the planet. Conversely, when CO2 levels fall, weathering slows, allowing CO2 to accumulate and warming the planet.

-

Weathering of Silicate Rocks: Silicate rocks (e.g.,

feldspar) undergo chemical weathering in the presence of

CO2 and water, producing dissolved ions such as

calcium (Ca2+), bicarbonate (HCO3-), and silica (SiO2).

Reaction: CaSiO3 (silicate rock) + 2CO2 + 3H2O → Ca2+ + 2HCO3- + SiO2 + H2O.

-

Transport to Oceans: The dissolved ions are transported

via rivers to the oceans.

-

Formation of Carbonate Minerals: Marine organisms use

the dissolved Ca2+ and HCO3- to form calcium carbonate (CaCO3)

shells and skeletons. When these organisms die, their shells

settle to the ocean floor, forming sedimentary rocks.

Reaction: Ca2+ + 2HCO3- → CaCO3 + CO2 + H2O.

-

Subduction and Metamorphism: Tectonic processes subduct

the oceanic crust, carrying carbonate sediments into Earth's

mantle. Under high pressure and temperature, these carbonates

undergo metamorphism, releasing CO2 back into the

atmosphere through volcanic eruptions.

Reaction: CaCO3 + SiO2 → CaSiO3 + CO2.

Currently, the pH of the ocean is approximately 8.1, but prior to the Industrial Revolution, the pH of the ocean was about 8.2. This difference of 0.1 pH is logarithmic, so with every 1 decrease in pH, the water is 10x more acidic. Changes in pH in the ocean change what carbonate species is found most. As pH decreases, we see less carbonate, then less bicarbonate, and ultimately, more carbonic acid.

It is thought that seawater pH in ancient oceans was as low as 6.5 to 7.0, which means that life may have developed in more acidic conditions than what is found today. This means that similarly, worlds with oceans more acidic than the one we have on Earth might still support life.

However, we do see on some Ocean Worlds such as Europa that the pH might be too low for significant life due to many oxidants. In fact, scientists have estimated that Europa's ocean could have a pH as low as 2.6. Learning more about Europa can tell us what limitations of pH could be on Earth, as well.